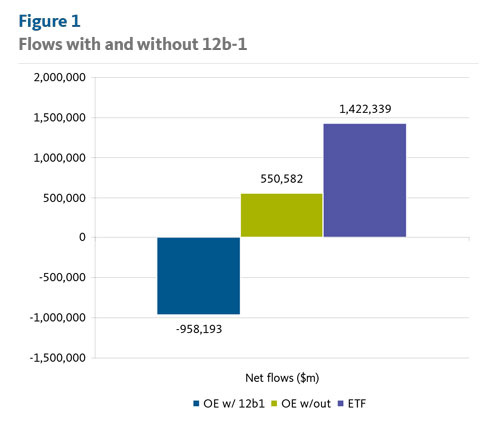

It looks increasingly like the distribution challenges of the next decade will not be between retail and institutional channels, but rather among different kinds of institutional funds, each with its own sort of omnibus economics. Absent 25 basis point 12b-1 fees, the question of who pays for distribution moves to the forefront: the end investor directly through intermediary account fees; the end-investor again, but this time via sub-TA and other non-12b-1 distribution fees embedded in the expense ratio, which, if adequately ‘leveled’ would not create a conflict of interest; or the fund manager, out of its own “legitimate profits” or various combinations of the above, remains to be answered. What’s settled (for now at least) is that 12b-1 fees seem to be going away, management fees are going down, and non-management fees are… to be determined.

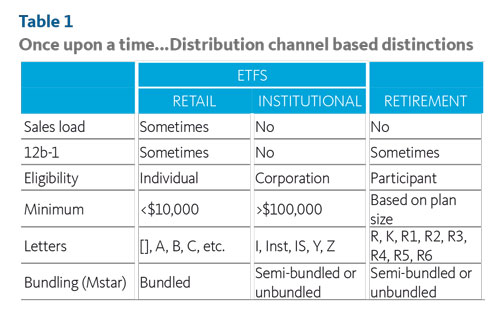

For fund directors, as always, the challenge, is to be sure that they are comparing “like to like,” so that the ratings and conclusions they derive from 15(c) reports can support the conclusions they reach. In the old world, that meant a relatively straightforward choice between focusing a retail share class, with a standardized 12b-1 fee or other charges that could be passed through to the distributor, or an institutional share classes with no such charges, and a third set of retirement share classes, distinguished by the size of the plan they were meant to serve, that could match either retail or institutional share classes.

Now it appears that the retail/institutional distinction is breaking down, with “instavidual” share classes taking over, designed for use either in a $25,000 asset allocation of an individual investor or in a $25 billion endowment portfolio. The traditional I share, with a management fee including some TA and sub-TA expenses fits the bill, as do most ETFs. At the same time, even after the demise of the DOL fiduciary rule, there is an increased demand from distributors who serve individuals for share classes free of any sort of distribution fees which might present a conflict of interest, from retirement plan consultants for share classes that externalize all plan service fees and from corporate investors for the cheapest available, all of which points toward some kind of clean share.

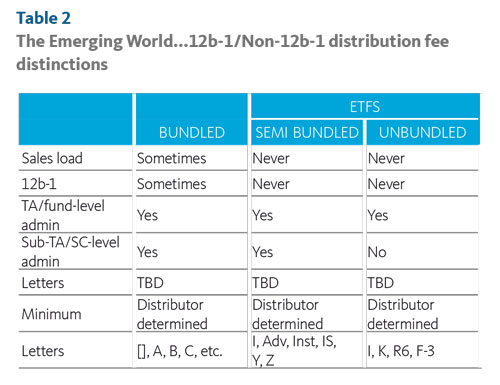

Broadridge expects that “retail,” “institutional,” and “retirement” designations may eventually disappear. The future state may well consist of share classes broken down by the inclusion (or exclusion) of embedded or non-12b-1 distribution fees, not according to investor type or situation. At that point, share class types would then fall into three buckets:

- Legacy share classes, which carry front or back-end loads (whether charged to all investors or not, and whether ‘level’ or not), as well as 12b-1 fees, and are characterized by Morningstar as “bundled.”

- Traditional open-end I shares and most ETFs, which have no loads, no 12b-1 fees, but which do have fund-level TA fees, retained by the fund manager to pay for administrative costs of the fund as a whole, across all share classes. These are classified by Morningstar as “semi-bundled” because they do include some fees paid by the investor to the fund company and passed to the distributor.

- Clean shares, in the strictest sense, which have only fund-level administrative and advisory fees (together, management), but not any share-class specific fees such as sub-TA which are collected by the distributor (and hence involve a potential conflict of interest), and are of course the cheapest available, and are labeled by Morningstar as “unbundled.”

Note that Lipper is expected to introduce similar share class distinctions in early 2019.

Morningstar has designated these three types as bundled, semi-bundled, and unbundled, the first corresponding to traditional A/B/C share classes; the second roughly matching up to “true” no-load funds (those without a 12b-1 fee), ordinary I shares, intended for large-scale investors, and, usually, the first retirement share class in a series without a 12b-1 fee (often R5). What counts as unbundled, according to Morningstar’s strict definition, are either the cheapest “institutional minus” share classes, which exclude sub-TA fees, the cheapest retirement share classes (usually R6), though the use of these has been extended to non-qualified accounts, as well as funds from families that, historically, have not paid any fees to distributors, most notably Vanguard.

Who Gets to Say What's Clean?

Morningstar’s bundled/semi-bundled/unbundled distinctions were unveiled in April 2018, but have not, in our opinion, been fully accepted by either asset managers or fund distributors. As of September 28, 2018, we would urge caution in treating the assignments of some share classes as “final,” based on our understanding of the operational structures of these funds. With those caveats in mind, we observe that there are currently 1,943 open-end fund share classes designated as unbundled, representing just 7% of the available share classes. However, these clean share classes hold more than $5 trillion, representing some 37% of all open-end assets. More than 10% of that amount represents net flows into Vanguard funds alone, despite the decision by some distributors to exclude Vanguard from their platforms because that firm does not pay any form of distribution fees. True, 574 of the 1,943, or about 30%, experienced net outflows in the last 12 months; but of the 1,370 remaining funds, which have had net inflows, only 159 (12%) are index funds. Put another way, the fact that actively-managed clean share funds are bucking the trend of outflows from active to passive suggests that price, rather than mandate, is driving asset flows, and the fact that Vanguard is receiving a substantial portion of these flows means that, in our view, it is not simply passive management but the combination of that and the absence of non-12b-1 distribution fees that is producing inflows for some and outflows for others.

Among ETFs, where 12b-1 fees have never been an issue, investment mandates are generally passive, and flows have generally been positive, the story is more about families than share classes: of the “big 5,” which make up 90% of ETF assets under management, only Vanguard— with 25% of the market — registers as unbundled; because of language in their prospectuses, or more exactly, the lack of prospectus language explicitly precluding payments to broker-dealers, Invesco, iShares, Schwab, and State Street are all semi-bundled, according to Morningstar.

Skeptics may wonder how much the semi-bundled/unbundled distinction matters, given that the DOL fiduciary rule is no more, the SEC’s proposed Best Interest regulation does not directly address clean shares but rather focuses on broker conduct and investor disclosure, and the Security and Exchange Commission’s “no-action” letter in response to the request by the Capital Group (American Funds) to offer clean shares was met with approval, but one that encompassed both their F-2 and R5 share classes (corresponding to traditional I shares, which the firm does not offer) as well as their F-3 and R6 share classes, which the firm designated as clean. Because the SEC in effect punted on the question of whether sub-TA fees rendered a share class not clean, firms operating within the broader SEC definition now offer their I shares as clean, although or despite the fact that Morningstar regards these as “semi-bundled,” that is, not clean, though cleaner than share classes with 12b-1 fees.

“Firms operating within the broader SEC definition now offer their I shares as clean, although, or despite, the fact that Morningstar regards these as ‘semi-bundled”

A Dilemma Directors Cannot Avoid

In an environment in which regulations are unclear, ratings agencies disagree with fund families, and investors are, as usual, confused by yet more talk of basis points, what is a director to do? On the one hand, they may now oversee two share classes, both of which the advisor presents to investors as clean. On the other hand, one of these share classes is notably cheaper than the other, precisely because it lacks a fee that the more expensive ‘clean’ share charges. That discrepancy, in turn, explains why some distributors (or distribution platforms) would logically demand one share class for their platform while others would demand the other one. Price-conscious purchasers (that is, purchasers) would understandably want to know why they were paying the higher price and anyone in a fiduciary capacity, or anyone putting their own fees on top of investment management fees would of course want to know why they were not getting the cheapest share class. Then too, the Gartenberg standards, involving the nature and quality of services received in exchange for any shareholder fees, could also be invoked here, requiring boards to understand more precisely how shareholders benefit from their services.

Adding to the difficulty, directors have to reconcile two competing obligations, which seem to conflict in the case of clean(er) share classes. The first is to ensure that the fees charged for the funds they oversee are reasonable, which in the current market, almost invariably means being lower than they have been historically. Adding to that pressure, directors now find it hard to dismiss passive funds as a different animal, not to be compared in price to active funds, because the market has told them otherwise. And, distribution channels are now so mixed up, that they cannot disregard the 800 pound low-cost gorilla in the room, Vanguard, as having an entirely different distribution structure. Nor can they easily overlook the fact that non-mutualized families such as BlackRock (iShares), privately held firms such as Fidelity, and advisory firms such as Edward Jones are now manufacturing their own clean shares. These for-profit firms can essentially provide asset management for next to nothing, instead reaping the benefits of scale and non-management services, leaving everyone else to fight for a diminishing number of slots on the product shelves of major distributors.

The second obligation of directors is to increase scale, providing benefits to shareholders, in the form of lower costs, and to the fund manager, in the form of greater revenue and hence profitability. But scale has never been a matter of just performance and expenses: it is also highly dependent on distribution. And, distributors, not surprisingly given the apparent demise of distribution fees, still expect to be paid, somehow, for the work they do to bring funds to investors. If a fund is well-priced and delivers good performance, but can’t get on a platform, then its status as “clean” is at best a moral victory: a clean share with no assets will close if its scale is not sufficient to provide profits.

“Raising fees, especially those that are paid by shareholders and thus also diminish returns, is likely to arouse scrutiny.”

Why can’t directors have it both ways: semi-bundled share classes for distributors who expect them, and fully unbundled clean shares for different platforms? Like most board issues, this one has both a legal and a business component. Legally, in a post-12b-1 fee era, directors are likely to be asked to raise fees to cover the sub-TA or non-12b-1 distribution costs that funds will now need to pay to be on the diminishing number of platforms available to them. Yet raising fees, especially those that are paid by shareholders and thus also diminish returns, is likely to arouse scrutiny. This probably unwanted attention is intensified by the fact that any such fee increases have to be, in Goldilocks terms, “just right.” If they are too high, such fees could be interpreted as “distribution in guise.” If they are too low, any discrepancies would have to come out of the management fee, either raising that when competitors are going in the opposite direction, or cutting into the fund manager’s profits at a time when revenues are squeezed.

Could Clean Shares be the First Step Toward a Wonderful World?

Stepping back, it’s important to recognize that the DOL Fiduciary rule was only part of the reason that fund firms were looking toward clean shares as a way to improve their businesses. While most of the attention on the shift from funds to ETFs has been on the fact that the former are (largely) actively managed and the latter are (largely) passively managed, what often gets overlooked is the advantages (to asset managers) of the expense and legal structure of the ETF. As mentioned by Capital Group in their original letter to the SEC which prompted the now well-known “no action” letter response from SEC Senior Counsel Rachel Loko, Morningstar was beginning to include ETFs in its fund ratings, a win for ETF providers but a loss for fund companies, whose ratings depended not on a single low cost share classes, but all share classes, including those with hefty non-management fees.

The Capital Group letter also implied that, not only did ETFs enjoy an advantage in a ratings system, they also had an operational advantage: whereas a fund company had to create a separate and distinct share class for each distribution platform, the same ETFs could, with a different commission structure, serve an investor with $100 a month or a major institution with $100 million. In other words, whereas ETFs started, and were thriving, with a single “share class,” funds started with a few, added more, and were now, in the case of American Funds, offering 17, including 3 for 529 plans and 8 for retirement plans.

“For Capital Group and others seeking to have their share classes declared clean, the clean share would be the share class to end all shares classes”

Our contention is that for Capital Group and others seeking to have their share classes declared clean, the clean share would be the share class to end all share classes, serving every market, and bringing to an end the proliferation of share classes that had already run out of letters of the alphabet. For an asset manager, a single, clean share class structure would put them on a level with ETF providers in terms of their obligations to distributors as well. Under a traditional share class structure, the fund company collects, but then passes through, much of the fees that it collects to third parties: the fund’s net expense ratio is higher than that of a comparable ETF, but the asset manager is no more profitable, because by law and practice, the fees it collects apart from the management cannot be a source of profit for the firm. And, as my colleague Jeff Tjornehoj has noted elsewhere, the “non-profit” Vanguard has a very lucrative patent on an operating structure that allows its ETFs to benefit from the scale of its open-end funds by operating as a share class of those funds, rather than as a free-standing vehicle.

In addition to removing fund companies from the business of collecting fees on behalf of third parties, clean shares also offer fund companies the opportunity to escape the distribution business, and all of the associated costs and liabilities that are involved. Clean shares could allow an asset manager to be just an asset manager, not a fund company. Working free of the legal and operational constraints entailed in being a distributor also enables an asset manager to operate much like it would in the UK, where clean shares completely replaced commission-based products. In that environment, asset managers have to offer clean shares, but can also offer “superclean” shares, that is, the same strategy, for at a lower price, to a specific distributor, akin to what an institutional manager might do to win separate account business. Thus, rather than paying for distribution by means of a fee imposed on the shareholder, which increases their cost and diminishes their return, the asset manager “pays” for distribution by lowering its management fee to a distributor that can offer considerable scale, without also having to lower their fee to other distributors, as would be the case in the US market, where legally the price for one must be the price for all. Since many American distributors, including some of the largest broker dealers and fund supermarkets, are unwilling to externalize distribution fees (by either charging them to investors explicitly or absorbing them into the firm’s own advisory fee, as all UK distributors had to do) clean shares remain the only way a ’40 Act fund manager can effectively discount its price to win business.

The move to “pure” asset managers by means of clean shares also makes sense in the current investment environment. More and more, investors buy portfolios, rather than individual funds, and so the sale of a strategy takes place at the home office level, not the individual broker’s office. In a nutshell, funds that are on the shelf and in the model garner assets; those that sit outside don’t.

What The Market Seems to be Saying

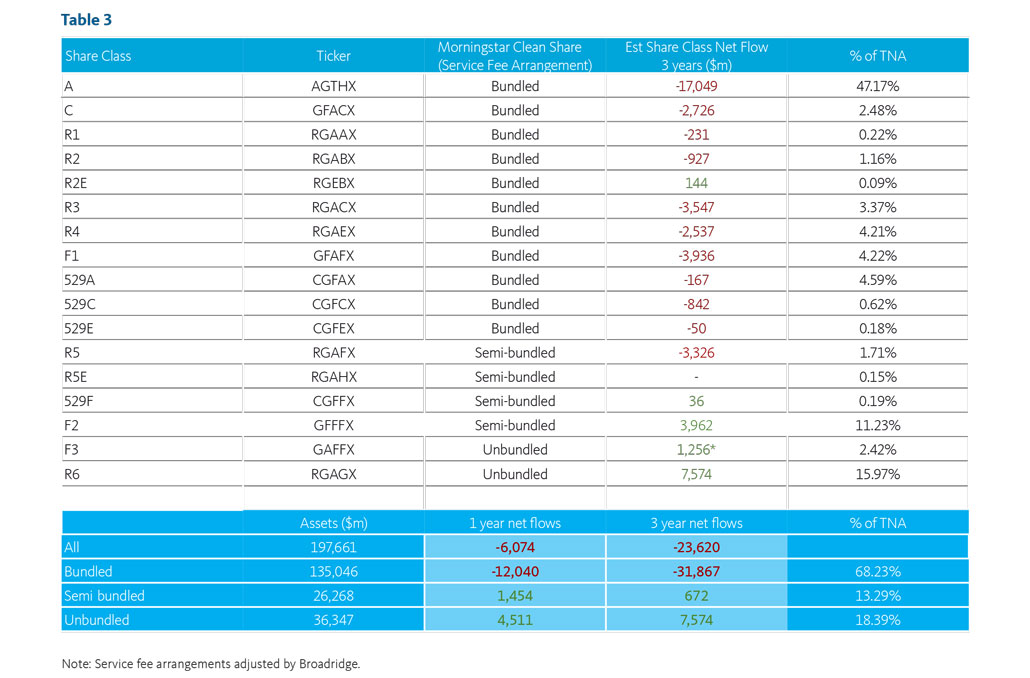

Regulations and corporate strategy aside, what is actually happening to clean shares out in the mutual fund marketplace? Is it possible that there are actually two markets, one for cleanish share classes, which still have sub-TA fees and revenue sharing, or what Morningstar would call semi-bundled and what old-timers would call I shares, and a second market for clean share classes? Thus, instead of having to ask “which?” directors can answer “both.” Take, for example, American Funds Growth Fund of America as a microcosm of the entire mutual fund marketplace. With nearly $200 billion in assets Growth Fund of American is the largest, actively managed fund in the US, and one from a family that offers bundled, semi-bundled, and unbundled share classes.

Like most actively-managed funds, this one is in outflows. But looking beneath the hood at where flows are coming out (and in) tells us something about the current state of the industry. Almost half of the fund’s assets are in two share classes designed for traditional commission-based brokerage, A and C. Altogether, two thirds of the fund’s assets are in what Morningstar would call bundled share classes, with 12b-1 fees, including five retirement share classes, three 529 share classes, and one advisory share class. Those share classes have shed nearly $32 billion in the past three years, despite the fact that the fund has outperformed the S&P 500 over that time. Meanwhile, the fund’s semi-bundled share classes (three retirement, one 529, and one advisory) have had (relatively) modest inflows of $673 million. In contrast, the fund’s two “clean” or unbundled share classes (F-3 for retail investors and R6 for retirement plans) have seen $7.6 billion in net inflows.

This admittedly small sample suggests that rather than seeing an exodus from active to passive funds, we are witnessing a grand migration from expensive share classes to cheaper ones. And, even among share classes without 12b-1 fees, the market for unbundled share classes is growing. So, even if the SEC granted a “pass” to what Morningstar would consider to be not fully clean share classes, it does seem that investors are savvy enough to see the difference, and are opting not just for cleaner share classes but for the cleanest. It likely helps that even someone unfamiliar with the arcane practices of fund distribution can make the basic distinction between cheap and cheapest: taking the cheaper options is much easier for a fiduciary or gatekeeper to justify than explaining why they selected the “almost cheapest” option, now that 12b-1 fees are diminishing in importance as a deciding factor as to who gets distribution where. And, someone looking at the marketplace from 30,000 feet could not help but notice that Vanguard, all of whose share classes are unbundled, had net flows of nearly $120 billion in the past 12 months, nearly three times the amount of its nearest rival Fidelity, which has not only launched its own clean shares (K) but also introduced four “zero fee” funds.

“Even if the SEC granted a ‘pass’ to what Morningstar would consider to be not fully clean share classes, it does seem that investors are savvy enough to see the difference”

Decisions for Directors

Along with distribution questions, boards also face the choice of continuing to use a legacy share class as the primary one in their 15(c) reports, or shifting to the kind of institutional share class that they believe represents the future of their business. And, within the latter option, they face a choice between semi-bundled (with sub-TA) share classes, and unbundled or clean share classes. The former is likely to have a longer track record than the latter, though the latter could well be gathering more assets in the current environment. That said, it is likely that semi-bundled share classes will come in for the greatest scrutiny, as they include the sort of fees that may have to be increased and, when paid out, could trigger “distribution in guise” concerns.

Of course, the options are not mutually exclusive: a board could continue to address one set of issues affecting bundled share classes, which could include outflows, 12b-1 fees, and existing sales agreements; another set of issues affecting “instavidual” share classes, that face competing demands for higher non-12b-1 fees and lower management fees, and still another set of issues related to the cheapest (and soon to be best performing) clean shares.

Not only do clean shares present expense challenges for directors, the removal of non-management fees also brings net performance much closer to gross performance, making it easier for a fund to beat its benchmark, but harder to attribute any underperformance to expenses required by distributors. Furthermore, we can anticipate that the rating systems used by Morningstar and other agencies which rely on net returns, will, on current trends, give share classes with the lowest fees an even more decisive advantage over expensive ones. While at first, per SEC and FINRA rules, the ‘child’ clean share will have to use the imputed returns of the oldest “parent’ share class of the fund, after three years, the funds’ rankings will come to be dominated by their more recent incarnation. In categories such as intermediate-term bond, in which long-term returns are dispersed over a more limited range than, say, emerging markets stock, it could be that the top 10% of the funds in a given category (those which Morningstar assigns five stars), are all clean shares, not because of superior investment management but because of the beneficial effects of lower fees on net returns.

Broadridge Practice

Starting in calendar year 2019, Broadridge will be able to incorporate Morningstar’s bundled/semi-bundled/unbundled share class distinctions into its peer group process. As noted, we anticipate these distinctions will displace traditional distribution and 12b-1 fee-based separations between retail, institutional, and retirement share classes. In general, this new practice will reduce the number of potential peers for a given fund by effectively reducing that set to one share class per fund. However, this more refined subset will more closely match the expense (and thus performance) characteristics of any subject fund. Then, too, the use of bundled/semi-bundled/unbundled markers will enable better comparisons across product types, such as ETFs and open-end funds, matching the current distribution environment in which portfolios can contain more than one product type. Finally, as standardized 12b-1 distribution fees become less common, and non-standardized non-12b-1 distribution fees become more important, we expect to offer more discrete breakdowns of transfer agent, sub-transfer agent, and other shareholder servicing and platform fees as well as more exact comparisons of these fees between fund families and among distributors within our 15(c) reports.

Items for Diretors to Consider:

- What will subsequent 15(c) reports look like? Will there be different sections for legacy retail share classes and newer, multi-purpose institutional share classes?

- If 12b-1 fees are going away, what processes are in place to measure distribution? How is the board addressing the two-fold danger of not getting enough distribution to grow assets and yet also not so high that they raise concerns about “distribution in guise?”

- Are there embedded liabilities in the expense structures of your legacy share classes? And, what are the plans for dealing with fixed costs as assets flow out in favor of other share classes?

- For active managers, is the issue your investment mandate or price? Put another way, would some other fee structure enable your fund to compete on cost with passive funds until performance patterns change?

- What are end investors being told, via marketing materials and disclosure, about the potential higher shareholder servicing fees they might be paying? And, how are the advantages of such fees presented, in terms of management fee breakpoints, that would produce a net savings to investors as assets increase?

- For open-end funds, does the fund’s current share class structure support the various channels that the fund will appear in, or does there need to be some sort of realignment?

- What will be the effects on shareholders, intermediaries, gatekeepers and fiduciaries as the “semi-bundled” and “unbundled” distinctions from Morningstar, and similar markers from Lipper, become more prevalent and widely known?