The 1934 Act created broad restrictions on corporate dishonesty and, through Section 10(b) and SEC Rule 10b-5, a cause of action for investors to sue. Traditionally, however, when an investor sued under Rule 10b-5 they had to show that they actually relied on a misleading statement in deciding to buy or sell a security. This was not easy to prove in court.

If an investor bought or sold a security soon after a misleading statement was made, it was hard to demonstrate in a legally sufficient manner that their decision was based on the misleading statement. Perhaps they had made the investment decision for their own reasons, or perhaps they were just following a herd of other investors. It was often difficult to prove that a specific investor even knew about a misleading statement, much less that they had relied on it.

The requirement of proving actual reliance was especially an obstacle to Rule 10b-5 class actions. Under Rule 23(b)(3) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, a class action for monetary damages is only allowed if “questions of law or fact common to class members predominate over any questions affecting only individual members”—in order words, if the class of people suing has the same core grievances and present largely the same legal issues. For most securities class actions based on Rule 10b-5, this was understood as requiring proof that all the members of the class had to some extent relied on misleading statements in making their trading decisions. As long as it was necessary to prove such individual reliance for an entire class of investors, securities class actions would fall short of the Rule 23(b)(3) commonality requirement and would be unlikely to succeed.

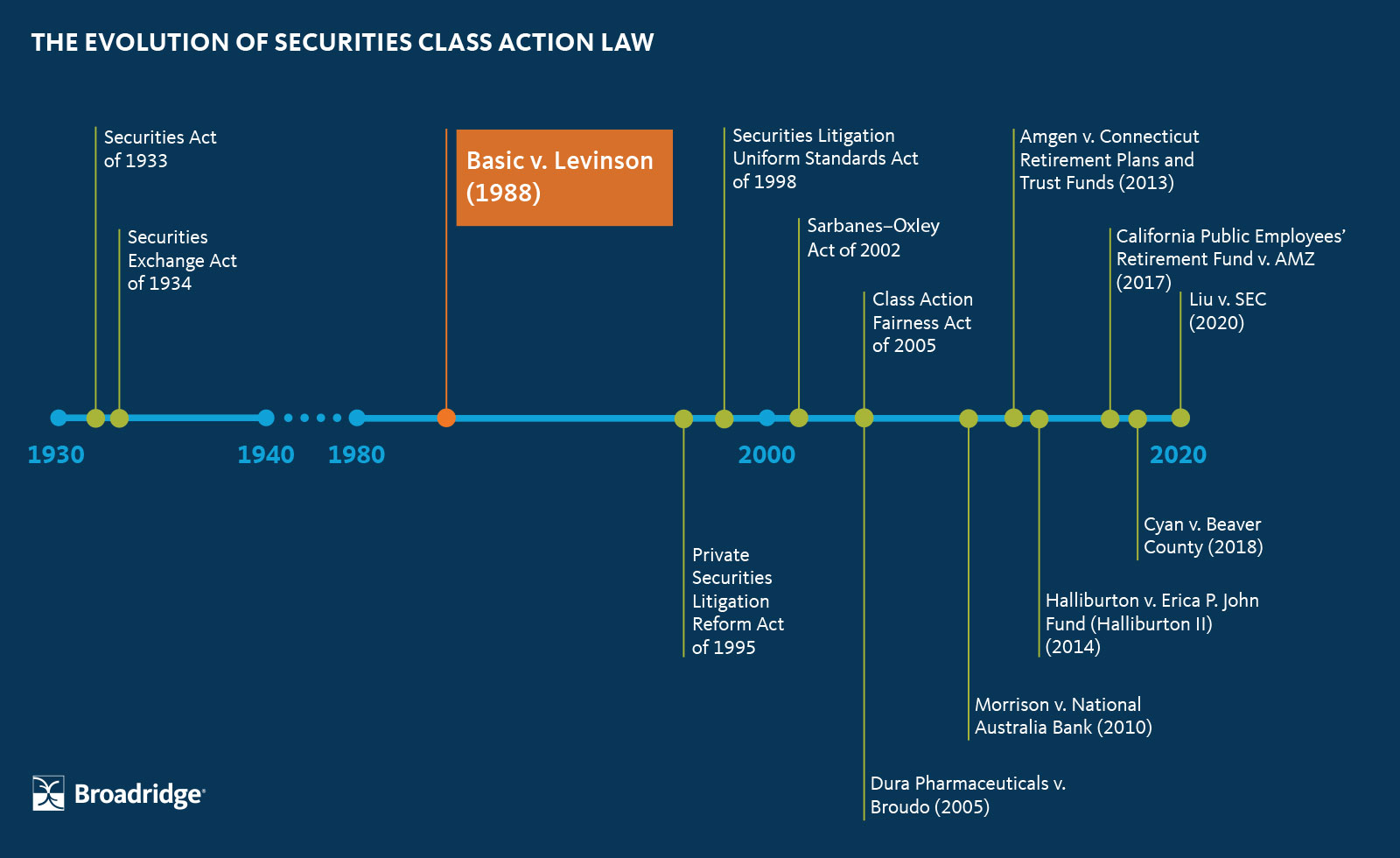

Basic v. Levinson (1988)

Impact

- Established the fraud on the market theory, which allows class actions to proceed without proof that all class members actually relied on a misleading statement

Beginning in 1976, Combustion Engineering, Inc. had discussions with Basic, Inc. concerning the possibility of acquiring Basic1. In 1977, the president of Basic publicly denied that any merger discussions had taken place. In the case that became known as Basic v. Levinson (1988), Basic was sued under Section 10(b) of the Securities Exchange Act and SEC Rule 10b-5, on the argument that its president’s false statements had artificially lowered the company’s stock price. This lawsuit was brought as a class action representing all investors who had sold Basic’s stock during a fourteen-month period following the false statements.

Given the size of the class, it would have been impossible to prove that all members of the class had learned about the false statements and actually relied on them. Therefore, the plaintiffs presented an alternative argument for certifying the class, called the fraud on the market theory. In a 4-2 decision, the Supreme Court accepted their argument.

The fraud on the market theory provides a different way to understand what it means for investors to rely on a misleading statement. A key assumption is that markets are quite good at incorporating new information into prices. Therefore, if a misleading statement is publicly known and material to the price of a security, and the security is traded in an “efficient market,” then the misleading information is assumed to be baked into the price. This theory also assumes that all investors who buy or sell a security are relying on the integrity of its price. Thus, the fraud on the market theory creates a presumption that merely by relying on the accuracy and validity of a stock price, an investor is inherently and unknowingly relying on a misleading statement.

The fraud on the market theory has never been more applicable than it is today. We now live in an age of social media, with information and news travelling practically at the speed of light. Statements by corporate executives cause publicly traded stock prices to move up or down almost immediately. Consider, for example, when on August 7, 2018, Elon Musk infamously tweeted “Am considering taking Tesla private at $420. Funding secured.” Although there was essentially no merit to the tweet, Tesla shares jumped 10%.

Halliburton II (2014)

Impact

- Upheld fraud on the market, ending speculation that Basic would be reversed

- Allowed defendants to introduce evidence to rebut the presumption of price impact under fraud on the market

Basic immediately led to a spike in securities class actions, and soon the majority of securities class actions were relying on the fraud on the market theory. But even as Basic became a foundational case in securities law, a surprising number of lawyers wondered if the Supreme Court might someday change its mind about the fraud on the market theory and overturn Basic.

One reason some lawyers doubted Basic is that it was a very unusual 4-2 decision. Three conservative justices did not participate in the case. Anthony Kennedy had not arrived at the court when the case was heard, William Rehnquist recused himself because his daughter’s law firm took part in the case, and Antonin Scalia recused himself without saying why he did so. Many lawyers believed that had these justices participated, they would have tipped the decision away from endorsing the fraud on the market theory.

More generally, the political and judicial climate changed in the 1990s and 2000s. As we will discuss in our next article, Congress took steps to limit class actions by steering them to be litigated in federal courts. Meanwhile, some commentators questioned whether the fraud on the market theory made sense2. The Supreme Court also appeared to become generally less friendly towards class actions over the years, as indicated by its decision to uphold arbitration agreements that waived the right to take part in a class action3.

In 2002, a class action was filed against Halliburton for making a series of false statements, allegedly made to inflate the company’s stock price, which led to a drop in the stock price after Halliburton made corrective disclosures. This case weaved through the courts for many years. It first came before the Supreme Court over an issue unrelated to fraud on the market4, was remanded, and came before the Supreme Court again in Halliburton II (2014).5

This time, Halliburton argued that the class should not be certified if it could affirmatively show that the misrepresentations had not impacted the price. The Supreme Court accepted this argument, thereby introducing a basis for rebutting the fraud on the market presumption. Defendants could now introduce evidence that the price had not changed as a result of the misleading statement. If they proved the price had not changed, they would overcome the presumption of reliance established by the fraud on the market theory.

Other than that, Halliburton II maintained the status quo. The Supreme Court had a perfect opportunity to modify the presumption of reliance established by the fraud on the market theory, and it chose not to do so. Although the Court acknowledged criticisms of the fraud on the market theory, it found that the theory remained reasonable and deserved respect as established precedent. This decision can also be understood as a clear message that if critics of securities class actions take issue with the fraud on the market theory, they have to take their arguments to Congress. Thus, Halliburton II put to rest years of uncertainty around Basic.