International Class Actions

Over the decades, an increasing number of class actions filed in the U.S. began to have an international focus. This was the inevitable result of an increasingly globalized economy. More than ever before, consumers were buying products from all over the world, companies were establishing international footholds, and investors were buying shares in companies based outside their home countries. The U.S. class action was an effective vehicle for adjudicating many international grievances, especially when compared to the weaker mechanisms for aggregate litigation in other countries.

In the context of securities fraud, class actions could be “foreign” in three major respects: there could be foreign investors in the class, foreign companies being sued, or a foreign exchange that the securities were transacted on. Class actions that were “foreign” in all three of these respects were known as “f-cubed” class actions.

Rule 10b-5 and the fraud on the market theory were understood as being very flexible in accommodating international securities litigation. Courts followed a vague standard in determining whether private Rule 10b-5 litigation could be brought in the U.S. in connection with transactions that were predominantly foreign: an issuer of securities could be liable if they had engaged in fraudulent conduct in the U.S. or if the fraud had substantial effects in the U.S1.This standard provided no clearly defined point at which a class action was so international in focus that it could no longer be litigated in the U.S. Even when the conduct, company, and exchange were all based outside the U.S., there was usually still room to argue that there were “substantial effects” in the U.S.

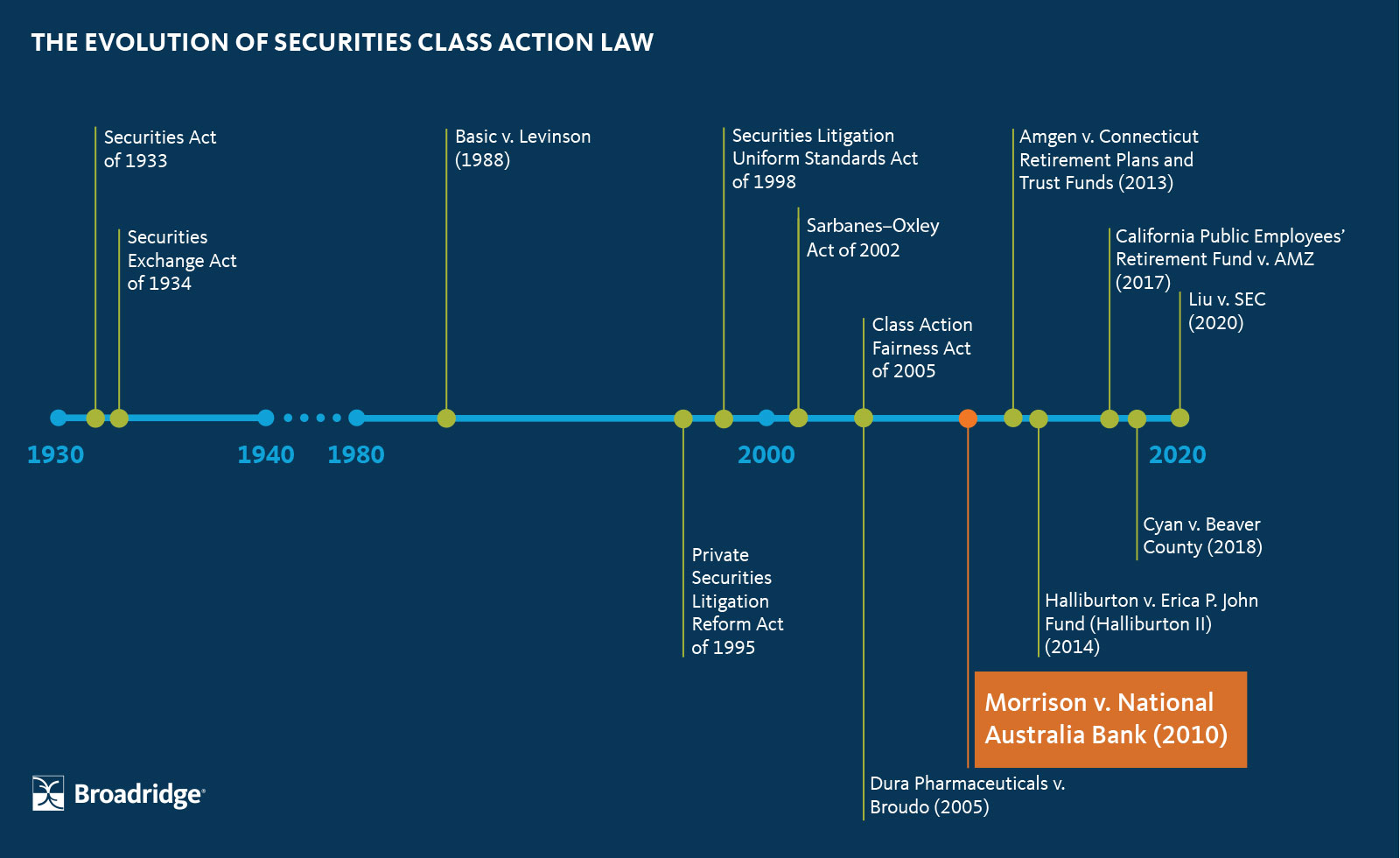

Morrison v. National Australia Bank (2010)

In 1998, National Australia Bank, an Australian company, acquired HomeSide Lending, a U.S. company2 . After errors in HomeSide’s accounting were discovered in 2001, National Australia Bank’s stock price fell and many of its investors lost money. A class action was filed against National Australia Bank, asserting several causes of action including a Rule 10b-5 claim. Morrison v. National Australia Bank initially began with three Australian plaintiffs and one U.S. plaintiff, but the U.S. plaintiff was excluded for a reason unrelated to this discussion—the district court determined that he had failed to properly state a legal claim. Thus, Morrison was reduced to only Australian plaintiffs. All these Australian plaintiffs had bought shares on the Australian Stock Exchange. Thus, these were foreign plaintiffs who had purchased stock on a foreign exchange and were suing a foreign company—an “f-cubed” claim. Morrison came before the Supreme Court over the question of whether “f-cubed” class actions could be brought under U.S. law.

An important subtext to Morrison was that adjudicating “f-cubed” class actions in the U.S. had an impact on regulation in other countries. Given the importance of the U.S. securities market, the possibility of Rule 10b-5 lawsuits in the U.S. implied that international companies had to consider taking additional precautions to abide by U.S. securities regulations. They had to do this in addition to, or even instead of, focusing on complying with the regulatory schemes of their own countries. When Morrison came before the Supreme Court, several countries made arguments to the Supreme Court (in the form of amicus briefs) that “f-cubed” claims should not be allowed out of respect for their sovereignty.

In a landmark opinion, the Supreme Court held that “f-cubed” claims cannot be brought under Section 10(b) and Rule 10b-5. The Court held that Section 10(b) and Rule 10b-5 claims can only be brought if they involve either a transaction that took place in the U.S. or the transaction of a security listed on a U.S. stock exchange. This conclusion was based on a general presumption that U.S. laws do not apply outside the U.S. unless they specifically state that they do. The Court also acknowledged the concerns about infringing on foreign regulation. It made the inference that if Congress had intended extraterritorial application of Section 10(b), which would have had extraordinary reach and the unusual effect of infringing on foreign regulation, it would have made its intentions clear.

Impact of Morrison

Before Morrison, many securities lawyers were discussing the advent of the “global class action,” anticipating that increasing numbers of class actions would be filed in the U.S. that were so international in focus as to essentially not be limited by national boundaries. One example of a global class action was In re Royal Ahold N.V. Securities and ERISA Litigation, a case that settled for $1.1 billion in 2006 over allegations of fraud brought against Royal Ahold, a Dutch company, after it made a downward restatement in profits of over $500 million3. The plaintiff class consisted of all people who had bought shares in the company, through either common stock or ADRs, over a period of over three and a half years—regardless of where they lived or where they bought their shares.

In re Vivendi Universal was a global class action that had the potential to result in an even bigger settlement4.This case involved a class of mostly foreign investors who had acquired shares in Vivendi, a French media conglomerate. Vivendi was found liable for lying to the public about its shaky finances, and at trial the jury awarded a judgement that would have resulted in a $9.3 billion payout to investors5. This judgement was appealed and remained pending at the time of the Morrison decision. Morrison extinguished most of the liability in Vivendi, and Vivendi ultimately settled for the comparatively meager sum of $26.4 million6 .

Viewed in this broader context, Morrison sent a strong message that the Supreme Court intended to limit excessively international litigation in the U.S., even beyond the specific scenario of “f-cubed” litigation. In the majority opinion, Justice Scalia expressed a concern that the U.S. had become “the Shangri–La of class-action litigation for lawyers representing those allegedly cheated in foreign securities markets.”7 In a concurring opinion, Justice Stevens wrote “this case has Australia written all over it.”8

Morrison has often been described as a game-changer, but perhaps it is more accurate to say that it nipped the global class action in the bud. Global class actions were actually quite rare both before and after Morrison9 . However, the Supreme Court likely feared that global class actions were about to take off, as it decided Morrison in the shadow of Royal Ahold and Vivendi.

Another part of Morrison’s legacy may be the rise of class actions around the world. Over the past decade, many countries have taken steps towards creating class action mechanisms or other forms of aggregate litigation. Most notably, the European Union is making some form of aggregate litigation on behalf of consumers available in all European countries10 .Morrison cannot account for all of these trends, as they go well beyond securities fraud, but nonetheless it was likely a contributing factor. If it had not been for Morrison, many more investors injured by securities fraud would have sought compensation in the U.S., and there would have been less pressure for other countries to create their own class action mechanisms.