Positive-Value Claimants and the “Wait and See” Strategy

Class actions serve multiple goals. Perhaps their most important purpose is to provide access to justice for people who otherwise would not obtain it. When a company engages in behavior such as securities fraud, selling an unsafe product, or false advertising, the harm done by the company is spread out among many victims. Even though the total amount of harm would warrant a lawsuit, most victims are not in a position to sue on an individual basis because the amount of money they can win is less than the cost of hiring a lawyer and going through the litigation process. These victims are sometimes referred to as “negative-value claimants” since their claims are likely to lose money when litigated individually. The class action device aggregates these claims and makes them worth the expense of litigation, and it thereby achieves access to justice for many individual claimants who could not afford to sue on their own.

It is important to recognize that class actions can help “positive-value claimants” as well. These are victims whose individual claims can win enough money to justify the costs of pursuing a lawsuit on their own. For example, large retirement funds can often afford to sue over significant cases of securities fraud on their own, so they do not need the class action device to have access to justice—but it still helps them. By aggregating their claims, class actions allow these victims to share the costs of litigation and increase their net compensation.

However, when it comes to positive-value claimants, class actions are a double-edged sword. Sometimes the class action will achieve a relatively small settlement, or a settlement that fails to recognize special circumstances that entitle a particular victim to greater compensation than other victims. In these situations, positive-value claimants may be better served by opting out of the class action settlement and pursuing their own lawsuit.

For a long time, many positive-value claimants who were included in securities class actions followed a “wait and see” strategy. They did not know at the outset of litigation how successful the class action would be, or what amount of compensation they would get. So these claimants waited for a class action to be filed, and they waited to see what the settlement would be. If the compensation they got from the settlement was more than the amount they expected to gain from an individual lawsuit, factoring in the expected costs of individual litigation, then they participated in the settlement. If the compensation they got from the settlement was lower than that what they could get on their own, they opted out of the settlement and filed their own lawsuit.

Statutes of Limitations and Statutes of Repose

There are two potential barriers to a “wait and see” strategy. A statute of limitations limits the amount of time a plaintiff can take to decide whether they will file a lawsuit. Statutes of limitations begin to run at the time when it becomes possible to file a lawsuit—typically, this is the time when the plaintiff suffered an injury. In contrast, a statute of repose limits the amount of time that the defendant is subjected to liability, so as to eventually release them from fear of litigation. A statute of repose begins to run at the time of the last act of wrongdoing by the defendant.

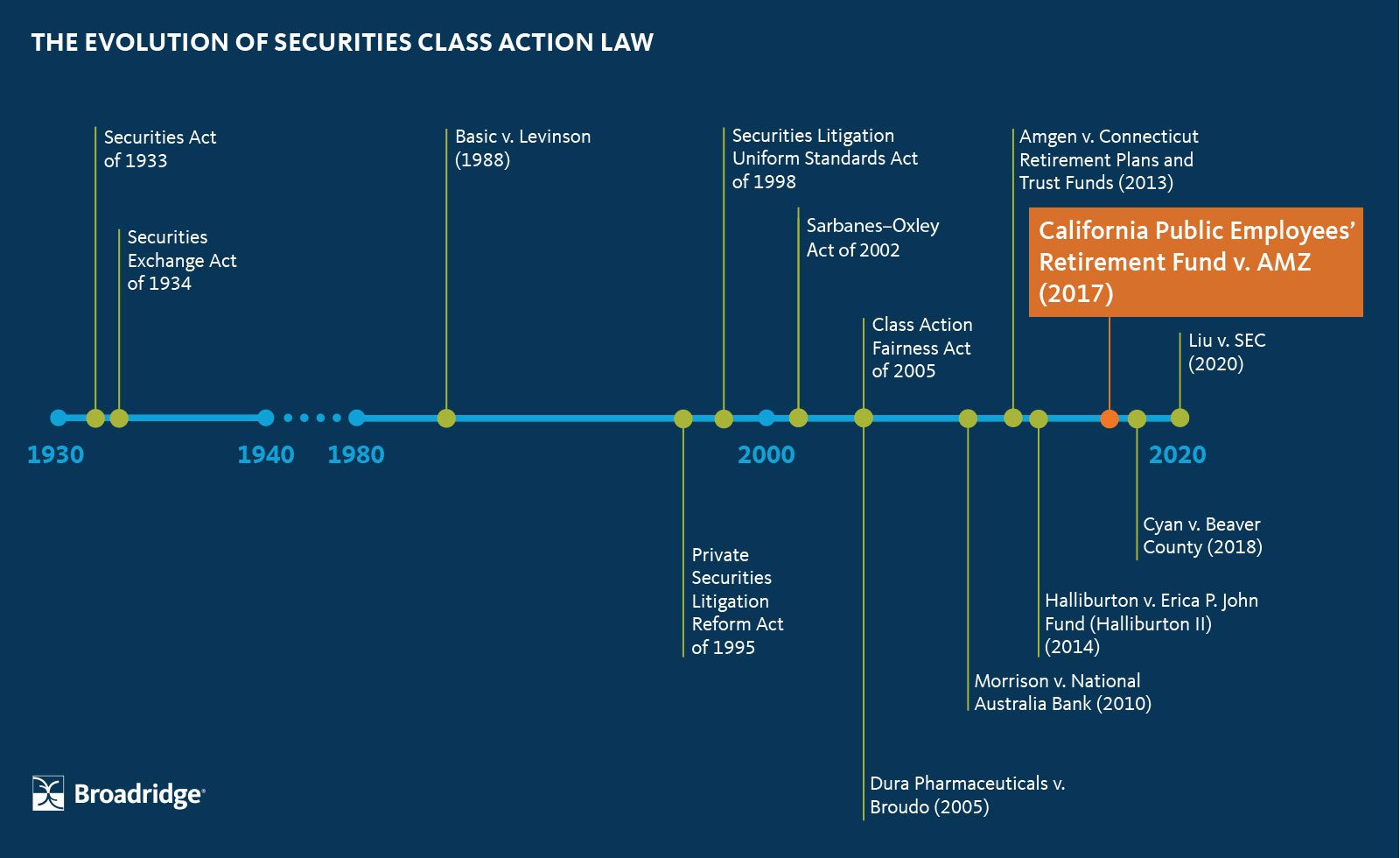

Securities fraud claims are subject to both statutes of limitations and statutes of repose. For Section 11 claims, the 1933 Act specifies a statute of limitations of one year and a statute of repose of three years. For Rule 10b-5 claims, the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 specifies a statute of limitations of two years and a statute of repose of five years.

Nonetheless, the “wait and see” strategy was still possible because judges “tolled” the statutes of limitations and statutes of repose, putting them on pause, while a class action was being litigated. This meant that a positive-value claimant could follow a “wait and see” strategy as long as a class action was filed before the statutes of limitations and repose ran out.

California Public Employees’ Retirement System v. ANZ (2017)

Lehman Brothers raised capital through public securities offerings in 2007 and 2008, soon before it filed for bankruptcy at the beginning of the 2008 financial crisis.1 California Public Employees’ Retirement System v. ANZ was a class action filed against a group of financial securities firms, including ANZ, in their capacity as underwriters for Lehman Brothers, based on a Section 11 claim for allegedly misleading statements in Lehman’s registration statement. The California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS), the largest public pension fund in the country, had purchased some of the securities at issue and filed its own lawsuit in 2011. When the class action achieved a settlement, CalPERS opted out. The defendants made a motion to have the case dismissed, pointing out that the statute of repose was three years and more than three years had passed. CalPERS argued that the class action had tolled the statute of repose.

The Supreme Court held that tolling does not apply to statutes of repose, and that it applies only to statutes of limitations. The Court emphasized that, unlike statutes of limitations, statutes of repose are intended to limit the defendant’s window of liability. Tolling the statute of repose while there is a pending class action, which could potentially last for years, would significantly expand the defendant’s liability. The Court took the position that such tolling was only appropriate if it was clear that Congress intended it that way, and it did not find clear evidence of such intent.

The implication of the CalPERS case is that organizations who suffered losses as a result of securities fraud must be aware of when the relevant statute of repose will expire, and they must choose whether to pursue an individual lawsuit before that time. If a securities class action has been filed, the statute of limitations is tolled but the statute of repose is not, which means that the “wait and see” strategy only works until the statute of repose expires. If an organization wants to file a viable individual lawsuit and does not do so before the statute of repose expires, they are left at the mercy of the settlement that results from the class action and have no other way to receive compensation. This also implies that the organization has less bargaining power in shaping the settlement as they are no longer able to credibly claim they will opt out. Depending on the amount of liability due to the organization, and the quality of the settlement, a failure to anticipate and understand the effect of a statute of repose may result in leaving a significant amount of money on the table.