Procedure and Substance

Class actions are a way to sue, not something to sue over. Therefore, any successful class action must overcome two challenges: it must establish that the case should be certified as a class action, which is a matter of legal procedure, and it must also establish that the case deserves to win, which is a matter of legal substance. In practice, these issues of procedure and substance are not always addressed in the same sequence, and there is always a complicated interplay between them. Still, a few generalizations can be made about how they come up in class action litigation.

After a complaint is filed, the defendant’s first move is usually to file a motion to dismiss, which is a challenge to whether the plaintiff’s legal claim is viable as a matter of substance. If the motion to dismiss fails, the next major step is usually the process of discovery, which can uncover new evidence relevant to the litigation. Discovery is painful and expensive for defendants. Sometimes defendants ask courts to initially limit discovery to the question of whether the class should be certified, in hopes that they can win on procedural grounds. Courts have significant leeway in choosing how to structure discovery.

Following discovery, the defendant has more opportunities to defeat the lawsuit before it goes to trial. They can file a motion for summary judgement, which is an argument that the plaintiff’s evidence is so weak on substantive grounds that no reasonable factfinder would find in their favor. The defendant also has an opportunity to rebut the plaintiff’s motion for class certification, by arguing that it is procedurally inappropriate to adjudicate the case as a class action.

Materiality

Class certification is a highly pivotal step in the litigation process, and judges take it very seriously. Although class certification is a procedural matter, it impacts substantive rights. Class members who are absent and do not opt out of the class action will be bound by the result, which means they will lose their ability to seek redress on their own. Judges are guided by Rule 23(a) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, which instructs them to decide whether the size and uniformity of the class justifies certification, as well as whether the lead plaintiff is an adequate representative who is typical of the class. When the lawsuit is over monetary damages, which it usually is, Rule 23(b)(3) instructs judges to determine whether issues common to the entire class predominate over individual issues. Satisfying this predominance requirement has been a pivotal issue in securities fraud litigation.

In the typical Rule 10b-5 securities fraud class action, Basic v. Levinson’s fraud on the market theory is the mechanism used for satisfying the predominance requirement. The centerpiece of a Rule 10b-5 case is proving that the plaintiffs relied on a misrepresentation in making an investment decision. Proving that a large class of investors knew and relied on a misrepresentation requires individualized evidence for each investor and is not possible to prove all at once for the entire class. At face value, this would seem to imply that predominance is not satisfied in Rule 10b-5 cases, as the key issue of reliance needs to be proven separately for all the investors in the class. But this is where the fraud on the market theory comes in: if a security is traded in an efficient market, and the company makes a misleading statement that is publicly known and material to the price of a security, it is presumed that the plaintiffs relied on the statement simply by relying on the integrity of the price of the security. Since the fraud on the market presumption applies to the entire class at once, it satisfies the predominance requirement.

Note that among the elements of the fraud on the market theory is the requirement the statement be material. This means that, to a reasonable investor, the information contained in the statement affects the value of the security. Also note that we are still discussing materiality as it relates to the Rule 23(b)(3) predominance requirement. Therefore, it would seem that courts must decide whether materiality is satisfied at the class certification stage, which would imply that materiality is a matter of procedure.

However, materiality also happens to be an element of the substantive claim under Section 10(b) and Rule 10b-5. In particular, the language of Rule 10b-5 creates liability for “an untrue statement of a material fact” or omitting to state “a material fact.” In other words, if the statement is misleading but it is not material, in the sense that it is not relevant to the value of the security in the eyes of a reasonable investor, then there is no legal liability. From this, it would seem that materiality must be proven at trial, which would imply that materiality is a matter of substance.

This sets up the dilemma: is materiality adjudicated at the class certification stage as a procedural issue, or can it be decided at the trial stage as a substantive issue? This question caused confusion among courts until it was finally settled by Amgen.

Now, you may be wondering how much this really matters. Regardless of when materiality comes up in the litigation process, it must be established for a Rule 10b-5 class action to be successful. In theory, the outcome is the same regardless of whether it is established at class certification or at trial.

However, it turns out that when materiality must be established matters a great deal, and the reason is that there are very few securities fraud class actions that go to trial. Trials are expensive, they are public spectacles that are embarrassing to defendants, and jury decisions are unpredictable. Thus, the class certification stage is critical. For defendants, defeating class certification is an important chance to get the case thrown out. For plaintiffs, winning class certification usually gives them enough leverage to get an adequate settlement, both because there is now an impending trial and because they gain the ability to negotiate on behalf of the entire class.

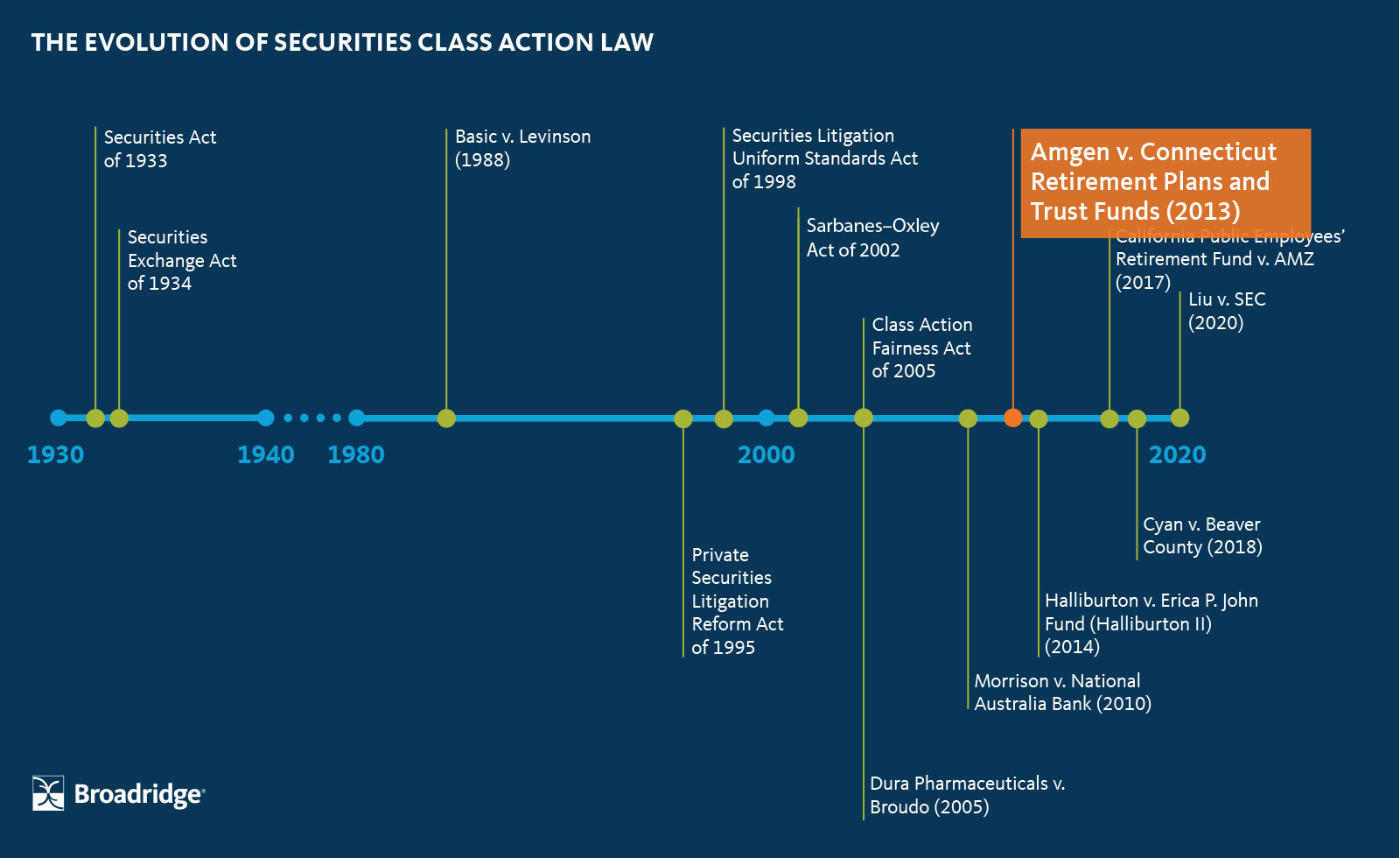

Amgen v. Connecticut Retirement Plans and Trust Funds

In Amgen v. Connecticut Retirement Plans and Trust Funds, Connecticut Retirement Plans and Trust Funds (CRPTF) filed a securities fraud complaint against Amgen, a biotechnology company, based on the allegation that Amgen had made misleading statements between 2004 and 2007 regarding the safety of two drugs.1 Amgen’s stock price had increased when these statements were made and it declined after the company released corrections, causing some investors to lose money. CRPTF sought class certification under the fraud on the market theory.

The issue that came before the Supreme Court was whether the class could be certified without proof of materiality. Amgen conceded that the other elements necessary for class certification were present, including an efficient market and the statements being of a public nature. However, Amgen argued that it had to be established that the statement was material in order for the fraud on the market presumption to be invoked because, by definition, an immaterial misleading statement would have no impact on the price in an efficient market, meaning that the fraud on the market theory would not be applicable.

The Supreme Court rejected Amgen’s argument, holding that materiality does not need to be proven at the class certification stage. The Court stressed that at the class certification stage, questions regarding the merits of the legal claim should be considered only to the extent necessary to determine whether the Rule 23 prerequisites are satisfied, including the predominance requirement. The Court found that materiality does not need to be established at class certification because it is not necessary for the determination that common questions predominate over individual questions. After all, the statements are found to be either material or not material as a common matter decided for the entire class, not as a matter that might be decided differently for certain plaintiffs.

However, the Court maintained that other aspects of the fraud on the market presumption, including market efficiency and the public nature of the statements, still do need to be established at the class certification stage. The difference is that if these fail to be established, individual claims based on Rule 10b-5 are still possible. As a result, these issues are relevant to the finding of predominance.

Although Amgen was quite a technical decision, its ultimate effect can be stated quite simply: it preserved the effectiveness of Rule 10b-5 class actions as a vehicle for obtaining favorable settlements for victims of securities fraud. Materiality is notoriously difficult to prove, and the other elements of the fraud on the market theory are nuanced enough already. If the Supreme Court had imposed a requirement that materiality must be established at the class certification stage, it would have been easier for defendants to defeat class actions at the outset of a lawsuit. Instead, the Supreme Court maintained the same level of difficulty for class certification. Given that any securities fraud class action that has been certified is likely to reach a settlement, most cases are able to achieve compensation for class members without ever actually litigating the issue of materiality.