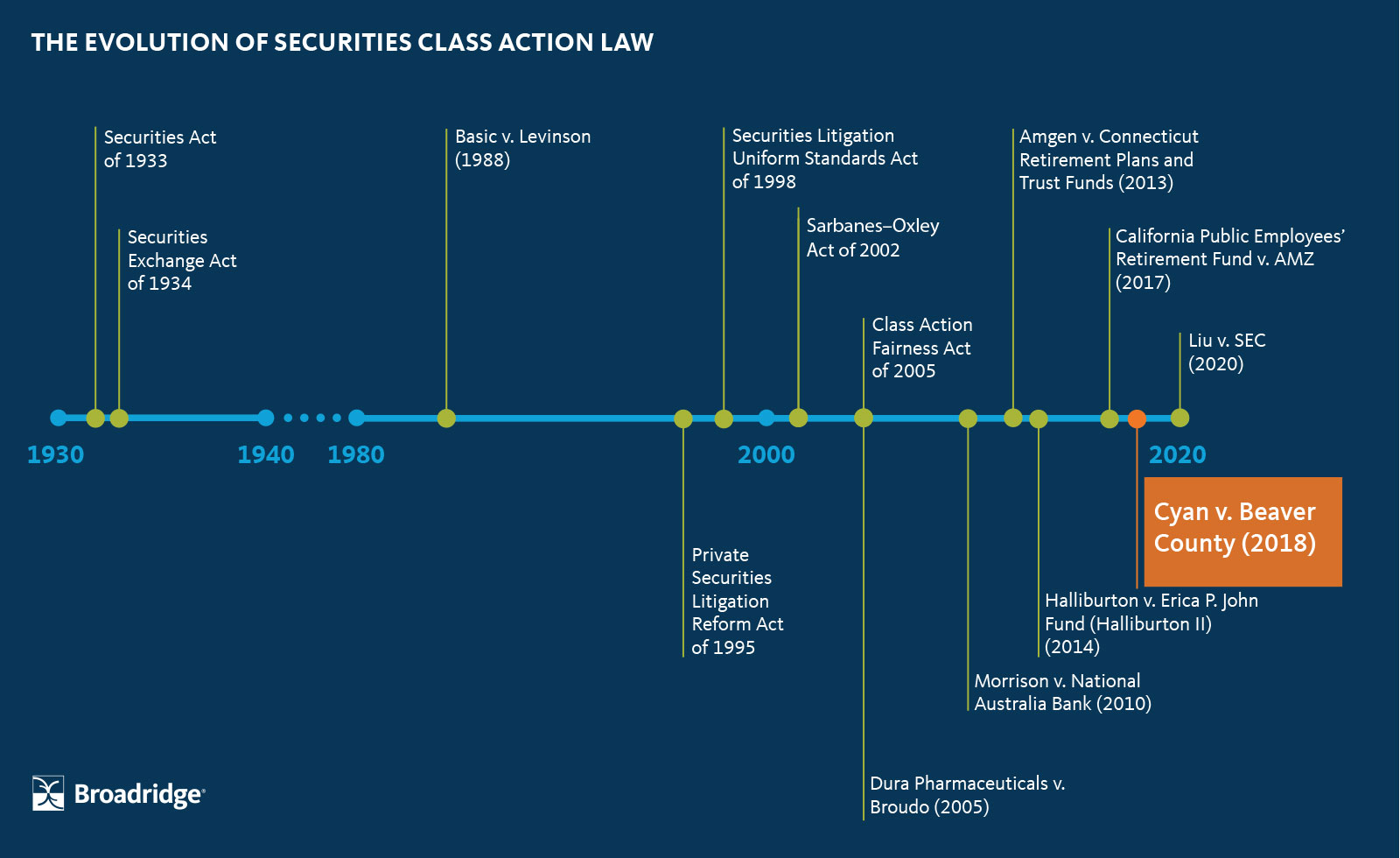

Federal and State Courts

When the Securities Litigation Uniform Standards Act (SLUSA) was passed in 1998, it moved Rule 10b-5 class actions to federal courts, but it was strangely unclear whether it also moved Section 11 class actions to federal courts. This basic question about the scope of SLUSA confused judges and lawyers for twenty years. In the oral argument for Cyan v. Beaver County, one Supreme Court justice described the text of SLUSA as "gibberish".1

Before Cyan, courts were inconsistent in how they dealt with this ambiguity in SLUSA. The 1933 Act had an anti-removal provision, which meant that claims under the 1933 Act could be litigated in state courts—but not if the law had been changed by SLUSA. When the Securities Litigation Uniform Standards Act (SLUSA) was passed in 1998, it added to the confusion. CAFA granted federal jurisdiction over some securities lawsuits, but not over others. There continues to be litigation over what areas were granted federal jurisdiction by CAFA and whether CAFA trumps the 1933 Act.2 It is also possible to argue that, taken together, the PSLRA, SLUSA, and CAFA are evidence of Congress’ intent to have virtually all securities class actions litigated in federal court. Indeed, it is quite reasonable to speculate that the only reason some securities class actions were excluded from CAFA was that Congress thought it had already handled them in the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act (PSLRA)and SLUSA.

Whether Section 11 claims can be litigated in state court is a crucial issue because, for several reasons, litigating a securities class action in state court tends to be advantageous to plaintiffs. To begin with, federal courts in general follow a more stringent pleading standard than most state courts.3 On top of that, in the context of securities litigation plaintiffs in federal court are bound by the heightened pleading requirements of the PSLRA: stating in specific terms what misleading statements have been made, claiming the defendant knew the statements were misleading, and claiming the statement caused them losses. Finally, being required to litigate in federal court means that plaintiffs do not have the luxury of choosing among multiple state courts in order to select the friendliest forum.

Cyan v. Beaver County (2018)

A group of investors brought a class action in California state court against Cyan, a telecommunications company, alleging that its registration statement contained material misstatements in violation of Section 11 of the 1933 Act.4 Cyan attempted to have the case removed to federal court, which is expected to be a more favorable forum. Cyan v. Beaver County came before the Supreme Court over the question that had caused so much confusion: can Section 11 cases be litigated in state court?

The Supreme Court finally settled the issue, holding that SLUSA does not apply to Section 11 claims, which means that Section 11 claims can be brought in state court. As a result, unlike for Rule 10b-5 claims, plaintiffs suing only based on Section 11 claims have an opportunity to avoid the heightened pleading standards of the PSLRA, along with other inconveniences of suing in federal court.

The Court unanimously signed on to an opinion written by Justice Kagan, which was a stalwart effort to make sense of SLUSA by following what appeared to be the most straightforward textual reading of the law. If the Court had taken a different interpretive approach, it may have decided Cyan differently. The interpretation that would have made the most structural sense would probably be to not allow state courts to retain jurisdiction over Section 11 claims, since they clearly do not have jurisdiction over Rule 10b-5 claims. If the Court had attempted to discern Congress’ intent, it also would not have found much evidence in legislative history that Congress intended this strange difference in how Section 11 and Rule 10b-5 claims are handled.

Securities Litigation After Cyan

Although Cyan finally clarified that Section 11 claims can be litigated in state court, it left securities class action law in a rather confusing state overall. First of all, SLUSA still bars state law claims that can instead be brought as federal law claims under Section 11. Thus, even though Cyan held that SLUSA allows state courts to retain jurisdiction, the actual law the state courts are interpreting is federal law. Meanwhile, for Rule 10b-5 claims, which are far more common than Section 11 claims, SLUSA still strips state courts of jurisdiction.

The net result is that although the vast majority of securities class actions will continue to be brought in federal courts, there is a carve-out for litigation that consists exclusively of Section 11 claims. Class actions that only allege fraud in a registration statement under Section 11 may still be adjudicated in state courts, and for such cases plaintiffs still have the opportunity to avoid the requirements of the PSLRA and select the most friendly state forum.

As one might expect, Cyan caused a sharp increase in Section 11 claims being filed in state court. A recent study found that 77 Section 11 cases were filed in state court in 2018-2019, compared to only 33 in 2016-2017.5 It is even more noteworthy that many of these Section 11 cases in state court have a parallel case in federal court—a lawsuit over the same misleading statements, with a different lead plaintiff and lead counsel, and which sometimes includes a Rule 10b-5 claim in addition to or instead of a Section 11 claim.6 The duplicative nature of these lawsuits raises the question of whether the outcome of Cyan is undermining efficiency and consistency in securities litigation. But in Cyan, as with many other areas of securities law, the Supreme Court sent a clear message that anyone who wants big changes in the law should take it up with Congress.