Assessment of Value

What to consider when considering performance - part 2 of 2

When evaluating a fund's performance, it's not just about comparing its returns to benchmarks or other funds. Whether you're conducting an Assessment of Value (AoV) under the U.K.'s Consumer Duty rules that focus on investor outcomes, or conducting general oversight as described by the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA), the analysis goes deeper than looking at returns versus peers and returns versus benchmarks.

Consumer Duty emphasizes whether the fund’s performance aligns with the goals investors have expressed. A fund might outperform its benchmark and be in the top 10% compared to peers, but it could still fall short under Consumer Duty and Assessment of Value if its risk level doesn't align with those stated goals.

A relevant, realistic criteria to review during the AoV process consists of a few elements:

- Comparative performance to the benchmark disclosed in a fund’s prospectus,

- Its relevant Investment Association (IA) sector

- Other funds with the same (or very similar) benchmark

Beyond looking at the net performance of a fund and various comparative performance metrics, the evaluation of risk measures can help you evaluate the value a fund provides to investors. The board can gain an indication of how skilled the portfolio management team is by evaluating the right risk measures, how closely (or not) a fund may be tracking an index, and how much overall risk is being taken to provide investment returns. A fund that exceeds benchmark performance with high relative risk may not, in fact, be providing value to an investor if the fund presents itself as minimizing risk to investors. Understanding the data is important, of equal importance is understanding what the fund says it will do and how it will do it for investors.

What data should we look at?

Although the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) is clear that net performance must be reviewed as part of the AoV process, it does not provide specifics as to the timeframe needed for that review, or what else that review should entail. Based on Broadridge’s work with U.S. boards for more than 30 years, we believe that displaying multiple time periods for performance is informative. In most cases, we will display one-, three-, five-, and ten-year performance. If a fund has not been around long enough to include for longer time periods, we will include since-inception performance.

With up to four time periods to look at, which is the most important (if that can be determined?). To start the review of performance, we recommend looking at the five-year net return unless there is a specific recommended holding period provided by the fund. This time period allows for the evaluation of a fund’s performance during multiple market cycles, and does not focus on short-term events that may impact a review of one-year returns. Including additional time periods allows for a review of consistency of approach, as well as the ability to review the impact of any changes that have occurred to the management philosophy in the shorter time periods.

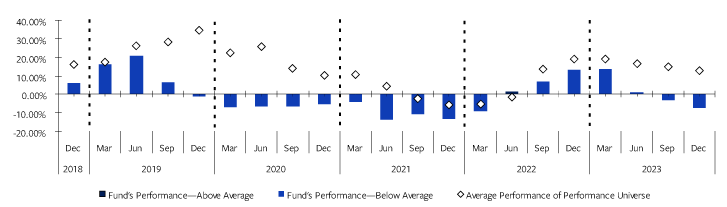

Performance consistency

Beyond looking at point in time performance comparisons, a review of performance consistency — or the fund’s batting average against its benchmark for an extended period of time — can prove useful when evaluation performance. A fund with a healthy batting average (percentage of time on a rolling monthly or quarterly basis, usually for a five-year time period, the fund has outperformed the benchmark) is likely to be considered to provide greater value than a fund that at a point in time is outperforming its benchmark but has returns that are very volatile.

Volatility vs. total return

There may be a need to pull in additional data and risk measures for evaluation of a unique fund. A fund intended to protect in a down market cycle may benefit from the inclusion of downside deviation or max drawdown as part of the performance review. Throughout the AoV process, both independent, non-executive directors (i-NEDS and executive directors should consider funds with a unique mandate and determine if special evaluation metrics are required.

Assessing risk

Performance evaluation is incomplete without understanding how much risk was involved in producing those returns. Risk may be defined in many ways, such as the probability of incurring a loss of capital or a loss beyond a predetermined amount or incurring loses relative to an index. Generally speaking, it’s the probability an investment’s return will differ from the expected return.

Although some risks may be defined before an investment is made (called ex ante risk), conventional fund governance is backward-looking and evaluates outcomes (ex post risk) rather than expectations. Academics and practitioners have developed calculations and statistics designed to explain or add context to fund performance as a result; of those, we find that five or six are used regularly.

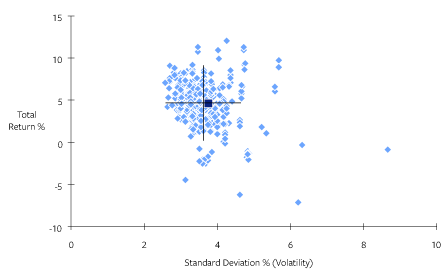

Risk/return measure: three-year periods-universe

- Standard deviation: The workhorse of risk measures, it quantifies the variation or dispersion of a time series and is usually calculated across 36 months of total return performance. May be compared to that of an index or a peer group median (often both) to assess how volatile a fund’s performance has been.

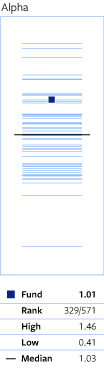

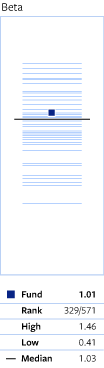

- Modern Portfolio Theory (“MPT”) statistics alpha, beta, and Sharpe: several others are used as well, these three are most commonly found together.

- Alpha: Often called the active return of an investment, alpha is calculated relative to a fund’s benchmark. If a fund’s return is even higher than its risk adjusted return, it is said to have “positive alpha.”

- Beta: Measures a fund’s volatility compared to its benchmark, such that a fund with a beta of 1.15 is expected to be 15% more volatile than its benchmark. Beta is typically around 1.0 and can be positive or negative.

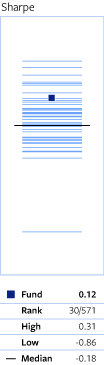

- Sharpe ratio: The ratio of excess return over standard deviation, it compares fund returns to a risk-free rate such as 3-month T-bills or gilts and not relative to its benchmark. Higher ratios are considered better.

- R-Squared: Often (though not always) used alongside the MPT statistics, it is the basis from which we can judge the relevance of alpha, beta, tracking error, and information ratio. R-Squared is the percentage of a fund’s movements explained by the benchmark. Figures closer to 1.0 give us more confidence about the other calculations.

- Tracking error: - The standard deviation of the difference between fund returns and the index, sometimes considered a fund’s index-relative consistency.

There are other risk measures used less often, but are still part of evaluating funds:

- Information ratio: Similar to tracking error but less common, it is the excess return of the fund versus its benchmark divided by its tracking error. Information ratio is sort of two tests in one: the degree of outperformance, and the consistency of outperformance.

- Active share: A relatively new entrant to the field of performance evaluation, it is the percentage of a portfolio that differs from its benchmark, where high active share means the fund is less like its index. Scores range from 0 to 100, using portfolio holdings and index constituents and weights for calculation. Active share is not readily available for non-equity funds and is somewhat limited, given that it looks at portfolio holdings at a specific point in time.

- Upside and Downside capture: Upside shows how a fund performed relative to its benchmark. To get this number, divide the fund’s monthly return by the benchmark return from each month the benchmark was up. Then multiply all figures to get an “average” capture as a percentage. Downside capture is similar, but only for those months when the benchmark was down.

We have all this data, now what?

One concern with looking at data is how much is too much, and whether looking at various performance measures makes it difficult to evaluate performance and shareholder value. Broadridge recommends starting with a single time period to use as the primary measure of fund performance, typically five-year net return. This comparison should be reviewed against each fund’s primary benchmark as well as a competitor group, typically the industry average (IA) Sector average. If a fund is performing well against these two measures, then typically a fund can be considered to be performing as expected and providing value.

If a fund is underperforming against these two metrics, however, an additional review of the performance will be useful for assessing value. Broadridge recommends a two-pronged approach when reviewing an underperforming fund. First, assessment various risk measures against the five-year period. Do the risk measure results correspond to what the fund states it is going to do as part of its investment objective? If so, then perhaps the fund is providing the value an investor is expecting.

Next, i-NEDS and the full board should look at other performance periods and overall trends. Does the fund’s more recent performance improve, indicating that work being done by the portfolio management team is rectifying areas of concern? In addition to more recent time periods, reviewing how the fund has performed on a rolling quarterly basis may indicate if the five-year period is being weighed down by one or two excessively bad periods, but is otherwise performing as expected. In a scenario like this, it may be decided once again that the fund is providing value.

Don’t forget to consider the challenge a fund had the beginning in terms of outperforming a market index.. All funds have inherent costs that benchmarks don’t, which handicaps a funds ability to outperform. Active and passive funds both come with costs. A market index has no costs associated with it; therefore, a fund with net performance (performance after all costs, including transaction charges, have been reduced from returns) even close to that of its market index is providing reasonable returns for investors.

Underperformance against a benchmark requires an understanding by the board of what is occurring. Underperformance against a benchmark and underperformance versus a comparative group, especially for multiple time periods, requires a more detailed evaluation and discussion to determine what (if any) actions need to be taken to provide investors greater value.

The evaluation of performance, and determining of a fund is providing any value, is difficult and requires both art and science. Directors need to look beyond just these performance metrics and also understand the intent and focus of each fund. This means spending time reading and understanding the investment objective as stated in the prospectus and other investor-centric materials. Performance evaluation also will require a dialogue between the board and the asset manager to make sure the fund is being managed in line with the stated objective. It is possible for a fund to underperform both its benchmark and competitors while still providing value while it is equally important for a fund to exceed it benchmark and competitors while in fact not providing the value an investor expects because it is not being managed in accordance with its stated investment objective.

Let’s talk about what’s next for you

Our representatives and specialists are ready with the solutions you need to advance your business.

Want to speak with a sales representative?

| Table Heading | |

|---|---|

| +1 800 353 0103 | North America |

| +442075513000 | EMEA |

| +65 6438 1144 | APAC |

Thank you.

Your sales rep submission has been received. One of our sales representatives will contact you soon.

Want to speak with a sales representative?

| Table Heading | |

|---|---|

| +1 800 353 0103 | North America |

| +442075513000 | EMEA |

| +65 6438 1144 | APAC |